Here’s a spoken word version of the keynote I gave at Biofabricate 2017.

Blog

Why Biotech Orchestration Strategy Beats Pure Invention: Lessons from Suzanne Lee’s Investment Reality Check

“Investors are now asking for off-take agreements, meaning that a brand needs to sign something that guarantees a purchase order of a certain quantity at a certain price for a certain duration. That’s the sort of thing you would normally expect in series A or series B, and now pre-seed startups are being asked for it!”

Suzanne Lee‘s latest interview in Formes de Luxe captures exactly what we’ve been tracking across dozens of conversations with major brands and biotech founders.

The rules of the game have changed.

The biotech investment landscape isn’t just “brutal” because of market conditions.

It’s brutal because the old playbook is broken.

Brands want materials that work better, not just cleaner.

Consumers want about results, not process stories.

This shift makes biotech orchestration exponentially more valuable than pure invention.

Most (not all) biotech founders are still thinking linearly: great science leads to great products leads to excellent outcomes.

But investors now want proof that someone can actually deliver at scale before they’ll write checks. They want to see partnerships, supply chain relationships, and commercial pathways that turn lab breakthroughs into market reality.

The companies that win in this environment aren’t necessarily the ones with the most elegant biology. They’re the ones that can navigate the complex ecosystem of manufacturers, regulators, brands, and consumers to create sustainable value chains. In other words, the biotech companies with an orchestration strategy.

We’re watching this pattern play out. The breakthrough moment isn’t when the science works — it’s when all the pieces of the commercial puzzle click into place.

As Suzanne notes, luxury brands know that they need alternatives to traditional materials, as regulatory pressure and climate change are rendering current supply chains unsustainable. But those brands won’t commit until they see fully orchestrated solutions, not just promising molecules.

This is the future of biotech commercialization. Not just better biology, but better business architecture. Biotech orchestration strategy.

Science Fiction Ideas Can Change the World

The Sci-fi Idea Bank is a spreadsheet of 3,567 sci-fi ideas, that proves, if you choose to believe it, that ideas for new technologies appear in science fiction first, and, can serve, for the ambitious, as a catalyst to bring Sci-fi to life. Vintage (like 1634 vintage!) and post-modern, it includes:

- bio-energy (1726),

- food tablets (1915),

- brain rejuvenation (1930),

- a scent organ (1932),

- a sobriety ray (1942),

- vat meat (1951), and

- DNA publishing (2011).

Among many other existing and to-be-developed product and company ideas compiled across 500 years of speculative fiction.

Not Boring‘s Packy McCormick admits – transparently – that he built the spreadsheet over a weekend using Technovelgy (“the best website on the Internet”) and a team of AI research assistants to demonstrate “it’s hard to find an example of a tech company whose product didn’t first appear in speculative fiction.” Inventing and writing down ideas is perhaps perceived as easier than executing ideas, bringing them into the physical world. But idea generation, developing characters who interact with novel ideas, inventions, technologies, in new situations and timelines, and grow (because there is no story if there’s no growth) during the course of the story is far from easy.

(I’ll admit, that as much as I read, I never read enough SF. And that admission aside, to me, even bad SF with a great idea is better than most other fiction. )

The SFIB is terrific at showing you ideas. It’s a brilliant why-didn’t-I-think-of-this spreadsheet.

The stats are nuts.

- It starts in 1634 for God’s sake.

- Of the 3567 ideas presented, 26% have been built.

- Those involving bits (32.4%) were more likely to be built than those involving atoms (23.7%).

- Author Philip K. Dick (of Blade Runner, Man in the High Castle and Minority Report and 43 other novels fame) generated more ideas (241) than any of the other novelists examined (Robert Heinlein is second).

A few days before McCormick released the SFIB, in her newsletter, author/journalist’s Annalee Newitz (Autonomous, The Terraformers) – who is not included in the SFIB – described “applied science fiction,” Neal Stephenson’s idea that we should write SF about solving big problems. According to Newitz, “futuristic stories don’t just exist on a continuum of dystopian to utopian. They are also on a problem-solving continuum, where on one side you have people writing about fixing broken systems – and on the other side you have people whose writing is all about admiring problems without suggesting any solutions.”

In other words, we need stories. We need stories about solving big problems with people fixing broken systems. And we need stories to help us process the changes, technologies, and possibilities of multiple unrealized futures and even to inspire us toward the futures we want.

In the 1970s, English punks adopted No Future as a motto to assert their generation had no future in front of it. Fifty years later, the punks that are still around are likely grandparents and the no future they probably turned out a lot better with than they expected. Perhaps it’s time No Future morphs into Which Futures? as we grapple with the acceleration of change. Societal dysfunction, divisiveness, doubt in institutions, and climate change are happening simultaneous to a great acceleration of positive technologies. I like saying we need every solution, everywhere, all at once.

McCormick points out that some ideas need underlying technologies, economics, probably, politics and hell, personal obsession, to be brought into reality. But still more than 70% of the ideas presented have yet to make their way into reality and at least a few are billion dollar ideas.

You can examine the SFIB and complain it’s not comprehensive enough (how could it possibly be?). One glaring issue is that the SFIB is mostly male, leaving out a wealth of contributors to science fiction from the likes of Octavia Butler and underrepresented non-English writing writers. Despite these limitations, the point of the admirable SFIB is to acknowledge speculative fiction as a source of ideas, be inspired by them, investigate them, then, if you’re so motivated, go make those that can be reality real.

There Will Be Dragons. Imagine. (Full Review)

So, here it is. And the question that might occur to you before you read or as you finish “How to Build a Dragon or Die Trying: A Satirical Look at Cutting Edge Science” is, Can we do it? Because when you get around a group of synthetic biologists, talk often turns to de-extinction projects or lead to speculation about building – or, if you insist, engineering – mythical creatures. The dragon, no surprise, is the favorite. And here is a funny, light, and accessible book by UC Davis professor and stem cell influencer, Paul Knoepfler and his daughter, Julie, who had started exploring the building of dragons as a junior high science fair project. The book not only gives us the instructions but begs the question: Should we do this?

But let’s take a step back, put things into context, and get you up to speed before I start throwing insider terms. We’re nearly 50 years into the biotechnology revolution and 20 years into the so-called Biotech Century. Probably without you realizing it, biotechnology delivers the majority of the top 25 drugs in the world and already touches your life almost every day: In the foods you eat, the clothes you wear, even the carpets you step on. The genetically engineered bio-economy supplies a healthy, but growing-so-fast-it-can’t-be-accurately-tracked three percent to the U.S. Gross Domestic Product.

Genetic engineering is getting easier, more accessible, and some would even say democratized while the means to do so are more able to do more. The synthetic biology industry is creating and delivering tools that promise to make the engineering of life as easy as Cut-Paste-Grow. Gene-editing with technologies like CRISPR is making all sorts of groovy genetic modifications more accurate. Smart countries around the world are investing in bioeconomy blueprints because governments expect biology as technology will a great economic driver. Need further proof? World-famous technology seed accelerator Y-Combinator started accepting biotechnology companies a few years back, and copycat incubators and accelerators are popping up everywhere. Not to mention that the proliferation of microbreweries puts every American within 10 miles of biotechnology-enabling fermentation infrastructure.

That all said, biotech is by no means easy. It’s not widespread. So don’t believe the hype just yet.

Applications of biological technologies can’t come fast enough: We need more biology to feed more people, revive habitats, keep us healthy, and even get us off-planet. We need those biotech applications you know, um, like yesterday. But this might be too much for the anti-GMO and biosecurity crowd since it’s easier for biotechnologies to fly under the radar.

But let’s quickly get back to building dragons. A frivolous undertaking, say you. Perhaps. But I think not.

We need to think bigger to take on those grand challenges, like land on Mars or save humanity from climate change. Building a dragon, I would suggest, is the perfect project.

Why? Because it’s a hella challenge (which I’ll get into shortly). And because one thing that hasn’t changed about us humans is our love of dragons or dragon-like creatures. These fire-breathing beasts have appeared in the mythology of nearly every culture of the world. The Knoepflers remind us that Western media glorifies European-type dragons that have wings, fly, breathe fire, and generally are bad-ass aggressive. We do rarely see cute dragons like the pain-in-the-ass Toothless and his ilk in the billion-dollar How to Train Your Dragon franchise, and the moderately aggressive Dragon that seduces Shrek’s sidekick Donkey and weirdly goes on to form a family with him – both are well-loved. But generally, we tend toward dragons like the trio that Game of Thrones’ Daenerys inherits, hatches, raises then sicks on deserving bad guys with her “Dracarys” (spoken with a measued lack of emotion) burning those bastards all to hell.

In contrast, Chinese (or Eastern) dragons are more commonly depicted as serpent- or snake-like with four legs. They control water, rainfall and typhoons and floods, and symbolize potent and auspicious powers. The dragon is the first animal of the 12-animal Chinese zodiac, and people born under that sign are considered life-long lucky. The only recent (and OK it’s not so recent) depiction of such a beast was the sidekick, shapeshifting, flying – and yes, fire-breathing – dragon, Dojo Kanojo Cho in the forgotten animated series Xiaolin Showdown

According to the Knoepflers, the distinction between Western and Eastern dragons is vital because “Asian dragons would be relatively easier to build. No fire or wings to worry about…[but] we want to focus on building a Western dragon because we want to make flying and fire-breathing lizards.” Get it?

Building a Western Dragon is a riskier, but we have a fetish for Sisyphian challenges, so what the hell, if we’re going to do this, LET’S DO THIS! AND DO IT BIG TIME.

Before we do, let’s review a few of the many things we’re going to be up against: There is no real-life, living model to work from – meaning, we have to start from scratch (a noble engineering challenge). There are no instructions (though “How to Build” as tongue-in-cheek as it claims to be offers us a rough plan). Producing fire biologically is not done in nature, nor is biological fire-proofing. The number of animal “chassis” to build from (or on) are numerous and choice could be crippling. Flight is a challenge. There will be safety considerations. Not to mention dragon intelligence and reproduction. And lest we forget, ugly, unwritten regulatory stuff. And of course, those pesky ethical issues.

Listen closely now: Even though building a dragon will require a hella large team of scientists, engineers, and specialists (and a fire department or fire-fighting expert because the dragon “may be especially prone to fire-breathing accidents when it is young), it will require (though Knoepflers don’t mention it) a communications team able to excite and sway the public. It will also require money. Lots and lots of money.

The dragon-building exercise, like the Genome Project Write (GP Write) that seeks to build entire genomes from scratch, will undoubtedly yield new technologies that can be applied (and no-doubt) monetized elsewhere.

The Knoepflers aren’t afraid to address and take apart the challenges in the face of the current state of science (CRISPR!). It is, no doubt, uncharted territory with the devil in the details, and it either grabs you, or it doesn’t. It grabbed me. But I also think it’s inevitable – hell, I spent almost ten years writing a children’s book series about kids that make it happen after adults fail. I laughed many times, out loud, at the Knoepfler’s absurd but necessary considerations. For example, “dragon moonshine” examines people with auto-brewery syndrome (who knew?) and debates whether ethanol production in our dragons would be a flammable alternative to the gut-produced methane or hydrogen gases they’d be using to produce fire. How to ignite that gas is debated whether using a red phosphorous-containing gizzard or flint or electrolytes, the electricity-producing cells that electric eels use a defense mechanism.

Where I can’t entirely agree with the Knoepflers is “With some training, our dragon could learn to release its electrical spark coordinately with breathing of flammable gasses… which might prove to be a more reliable way to generate repeated bouts of fire-breathing.” I do like that better than grinding teeth and am of the opinion that dragon fire should be triggered by a hormonal flight or fight response in a fit of anger. Careful now.

There is enough in HOW TO BUILD to obsess the true, mainlining dragon-builder for a godly amount of time.

The Knoefplers do a good job considering, for example, all the ways things could go wrong. “Getting it wrong and an unfortunate mishap is deadly to onlookers. Our dragon could even die due to such a mistake. Small understatement.

You might, in reading this, form an opinion on how or whether this will go down. This building of dragons. IRL. Here’s mine:

Someone we know (yes, you probably know this person) will set up a garage lab or a company to start making it happen.

They’ll come out of alpha with the cell biology to build electricity-conducting wires that can be amped high enough to create the spark that can light the flammable gas. They’ll show that DNA grown on the surface of scales is fireproof (the DNA is). They’ll get funding and make the mistake of going public too soon. This will spark outrage and require a pivot – in story at least – which, not-ironically, will attract even more funding. (You know how that story goes.) New tools and techniques will emerge, come close to, but never reach commercialization.

Bleeding cash, our dragon-building company will try self-funding via a direct-to-consumer subscription service that gets kids around the world addicted to the idea that they too – with enough money – own their own pet dragon. (“Mommy, please! Poppy’s mom let her have one.”) The company will crash and burn spectacularly to the joy of detractors, fundamentalists, the anti-GMO crowd, and parents everywhere. They will breathe a sigh of relief, “Where would we put that damn dragon anyway?” Over time, those dragon-addicted kids will be heart-broken. But some will go on to start their dragon-building startups. Soon enough, dragons. Everywhere. A menace.

Until that happens, we have Knoepfler and Knoepfler’s book, which I predict more than a few will read as a set of instructions (or instructions for instructions). So let’s pause, smile, and remember the dragons we’ve read about, imagine those we’ll build, and give thanks to the daughter and father team that gave us this gift of a book to read and ponder.

# # #

There Will Be Dragons. Imagine.

Excerpt from an unpublished review of “How to Build a Dragon or Die Trying: A Satirical Look at Cutting Edge Science.”

There is enough in HOW TO BUILD A DRAGON OR DIE TRYING to obsess the true, mainlining dragon-builder for a godly amount of time. The Knoefplers do a good job considering, for example, all the ways things could go wrong. “Getting it wrong and an unfortunate mishap is deadly to onlookers. Our dragon could even die due to such a mistake.” Small understatement.

You might, in reading this, form an opinion on how or whether this will go down. This building of dragons. IRL.

Here’s mine: Someone we know (yes, you probably know this person) will set up a garage lab or a company to start making it happen. They’ll come out of alpha with the cell biology to build electricity-conducting wires that can be amped high enough to create the spark that can light the flammable gas. They’ll show that DNA grown on the surface of scales is fireproof (the DNA is). They’ll get funding and make the mistake of going public too soon. This will spark outrage and require a pivot – in story at least – which, not-ironically, will attract even more funding. (You know how that story goes.) New tools and techniques will emerge, come close to, but never reach commercialization.

Bleeding cash, our dragon-building company will try self-funding via a direct-to-consumer subscription service that gets kids around the world addicted to the idea that they too – with enough money – own their own pet dragon. (“Mommy, please! Poppy’s mom let her have one.”) The company will crash and burn spectacularly to the joy of detractors, fundamentalists, the anti-GMO crowd, and parents everywhere. They will breathe a sigh of relief, “Where would we put that damn dragon anyway?” Over time, those dragon-addicted kids will be heart-broken. But some will go on to start their dragon-building startups. Soon enough, dragons. Everywhere. A menace.

Until that happens, we have Knoepfler and Knoepfler’s book, which I predict more than a few will read as a set of instructions (or instructions for instructions). So let’s pause, smile, and remember the dragons we’ve read about, imagine those we’ll build, and give thanks to the daughter and father team that gave us this gift of a book to read and ponder.

Here’s the full review.

My Coronavirus Experience

This morning, I walked out of our apartment at 930am, running late. I reached the corner and was about to turn onto Fourth Avenue, when a guy looked at me and held his gaze for longer than comfortable. He was staring at my chin. I stared back, realized I had walked out without a mask. Even though I’ve been religious about wearing a mask, social distancing, and avoiding crowds, I still walk out of the house without a mask.

Yet, the whole time I felt that general sense of fatigue. No matter how much I slept, I kept feeling tired. Because I was sleeping on-off all day long, my insomnia returned, so my body not only was fighting the coronavirus, it was also trying to recover from less sleep.

Last March, I had a conversation with Daisy Robinton following her recovery from COVID19. Daisy’s a neuroscientist who’s also a fitness model. She’s someone that takes her fitness and health seriously. She told me that on Day 7 of her infection, she couldn’t get enough air, didn’t think she would breathe again, was ready to give up. A coupla days later, she was better.

The $100 Million Science Media Fund

For this year’s SynBioBeta conference, Data Collective founder and investor Matt Ocko hosted a panel on Abundance and Scarcity. Matt backs entrepreneurs attacking trillion-dollar problems to “amplify capitalism’s benefits and reduce its costs to society.” In Matt’s own words, his team is creating a future of “abundance, comity, and amity.”

Matt invited artist and storyteller Taryn Southern and me to participate. During the panel, he asked Taryn what she would do with $100 million[1] to promote the positive, exponential technologies now changing the world.

Taryn answered she would first look for creative applications of the technologies, then develop narratives based on desired outcomes. She reminded us technologies must put us and the technology at the center of a Hero’s Journey. Tactically, she said she would create 50 to 100 series and films that tell the stories of technologies for specific audiences. From this collection, Taryn would slice and dice the content into smaller pieces to create a marketing content funnel.

I said if this were the case, I’d join Taryn. Then she said the two of us would work together for The Cause.

The World of Abundance

We are close to living in a world of abundance. The energy, food, information, and materials sectors are being disrupted at unprecedented speed and scale. Access is improving while costs are falling.

But you’d never know it.

That’s because we humans are wired to pay attention to the negative. Our ancestors’ brains evolved a “negativity bias.” Our very survival depended on our ability to avoid danger and respond to it. When we hear a bunch of good news and a little bad, we pay more attention to the bad. It’s just our nature.

The media and politicians understand this. They focus on and leverage our negativity bias to increase clicks, increase revenues, and increase votes. (If you haven’t seen it, take the time now to watch the Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma.) Positive stories don’t sell, or so the popular wisdom goes.

But We’ve Got This

We can, however, make a difference through storytelling and a willingness to leverage negativity bias to tell stories about our abundant futures.

In other words, we can use existing tools and create some of our own to paint a positive vision of the future to help people understand the better world that is just around the corner.

So let’s start with that end in mind: A positive vision of tomorrow. (Several visions. Because there are many possibilities in front of us.)

Since this is ultimately a marketing campaign, that vision, Our Grand Strategy, is our starting point.

Last year, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez presented her vision for the future were we to enact the Green New Deal. Last week, Naomi Klein presented the sequel – The Years of Repair. These aspirational narratives are examples of what our positive visions of tomorrow could look like.

Our Vision Needs to Be Simple.

We all want a bunch of things. During the panel, I mentioned we could use the $100 million fund to tell stories on how technologies satisfy Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. That starts with clean water and air, food, and shelter—the most basic needs we humans have.

Right now, people are afraid. Afraid of the future. Afraid of the uncertainty. Afraid of politics. And afraid of science and technology.

Our job as storytellers is to counter that fear, by putting people at the center of positive futures and inviting them to come along for the ride. We need to help people see themselves as part of that future.

So, I’d say, “Hey Matt, we’re going to take that money and promote multiple visions. We’ll test our messages in social media, find what people actually care about, and course-correct as needed to make sure our stories resonate.”

We have to do this if we want to build our audience and avoid creating another Quibi-like failure.[2]

Are you with me so far?

Good. We’ve got our vision. Now we can get into our Tactics.

Here are a few:

Create Symbols

Every great brand has a recognizable symbol. Think of Apple’s apple, the Amazon smile, the Nike Swoosh, the red and white Coca Cola logo. They are recognizable everywhere.

We need visual images to associate with our movement(s).

Why?

Because seeing our symbols gives people a sense that something large and well-organized is happening. Logos are tangible; they imbue abstract ideas with reality.

In the 1930s, at the height of the Great Depression, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, created the American New Deal Agency, also called The Works Progress Administration. One of the WPA’s most famous project, The Federal Project Number One employed musicians, artists, writers, actors and directors. They created thousands of poster designs including several to commemorate the National Parks.

Two years ago, NASA released a series of posters celebrating space tourism. More recently, Green New Deal proponents released a series of posters that reference FDR’s New Deal, specifically, the Works Progress Administration.

These images are important because our subconscious minds think in pictures and posters spark people’s imaginations. They get people talking.

We need images like these to show us the world of tech-driven abundance: A world of precision fermentation breweries surrounded by vast forests. Cities lush with vegetation and solar panels sprouting from rooftops. Kids staring wide-eyed through shop windows at phones growing like tulips.

Our images must be cool enough that kids and teenagers will want to hang them in their rooms. And they need to be available in every format.

Enlist the Next Generation

Taryn mentioned the importance of engaging young people. Of getting them interested in entering the fields that will make our future positive. We’re doing this work to create a better future. For that reason, at least some of our storytelling needs to be aimed at kids.

C16 Biosciences‘ CEO, Shara Ticku, recently told the story of receiving notes from school-aged children. The kids are happy her company is working to preserve the rain forests and save the habitats of orangutans and cheetahs. (C16 brews palm oil in yeast to stop deforestation.)

Kids’ media consumption habits are ever-changing, so our efforts need to include an endless stream of YouTube and Twitch videos. When and if new platforms arise, we need to engage with them quickly.

That means, as Taryn mentioned, putting animated series into production, writing picture and middle grade books, and promoting authors who are doing this work. If we find none, we will commission them.

There are gaps here, opportunities to fill in missing parts of the narrative. I know because I’ve witnessed it first-hand as my sons were growing up and consuming media. In fact, I wrote my Dragons Burn series to get middle graders interested in engineering biology because I only ever came across one reference to biotech in kidlit.

Work With Game Developers

Speaking of kids, we would fail in conveying our message if we did not target game developers. The truth is that U.S. children spend as much time in video games as they do at school. They’re receiving a separate game-driven education in creativity, problem-solving, socialization and collaboration, and critical thinking.

Even before the Age of COVID, the gaming industry was larger than the movie, film, and music industries combined. And now, thanks to the lockdowns, COVID has made nearly everyone a gamer of sorts.

IMHO, if you want to lead the world, you must involve the gaming industry. Its influence is that important.

A few years ago, in her TED Talk, Jane McGonigal suggested gaming could make the world a better place. She said games allow players to be their “best selves.”

Our campaign should target game makers, encouraging them to incorporate our positive messages and visuals. Even if they are just seen in fleeting moments while building that first cabin in Minecraft, riding that meteorite into the Fortnite map, or shooting up the enemy in Call of Duty.

If we don’t get traction, we could always start or even buy a game studio.

Create Podcasts and Courses.

Taryn mentioned the need to create lots of media in many formats. Podcast listenership, for example, continues to grow and needs to be part of the strategy.

A few weeks ago, A16Z investor Vijay Pande noted there was a gap in the marketplace for biotech-focused podcasts. A16Z launched Bio Eats World. This follows SynBioBeta‘s podcast and Ginkgo Bioworks Ferment.tv video series.

We need more of these.

So we will create two kinds – the purely factual like Bio Eats World and Ferment.tv, and fiction audio series like The Message, a fiction series sponsored by General Electric.

COVID is accelerating massive changes in education. Schools and universities have gone virtual. Companies have started to emphasize skills over degrees. Education platforms like Coursera, Udemy, and LinkedIn have seen their user numbers multiply. And we’re only at the beginning of this trend.

As part of our campaign, we will create courses that introduce biotechnology (Biotech for Non-Scientists), bio-manufacturing, clean energy, fermentation, free broadband, etc. But we will develop courses that are a lot more fun and engaging than the usual fare on these platforms.

Hell, we might even create our own platform for these.

Recruit Social Media Influencers

Do you doubt the power of social media?

This past month, a Tiktok creator, Nathan Apodaca, posted a video of riding a longboard to work while drinking a bottle of OceanSpray cranberry juice, and jamming to Fleetwood Mac’s “Dreams.” That brief video from a virtually unknown creator resulted in:

- 4.3 million views in less than 24 hours on TikTok alone; the current view count is more than 25 million views and rising

- Ocean Spray sales through the roof

- Fleetwood Mac’s song in the Top 10 after 40 years (and a copycat video from Mike Fleetwood)

- A new cranberry-colored car for Apodaca from OceanSpray, and

- A copycat video from Ocean Spray’s CEO, Tom Hayes, garnering more than 1.6 million views at the time of this publishing

Other influencers on Tiktok have explained the prevalence of mental health (Dr Julie Smith) and how to make your mask fit better (Dr. Olivia). Bear in mind this platform did not exist in the US just two years ago.

We will recruit social influencers to spread our message.

When I asked my 20-year-old niece Violeta Roth what makes TikTok videos go viral, she told me shock value helps. She sent me an audio clip of suggestions that could’ve been taken from Made to Stick:

Keep it short and straightforward, Elicit curiosity (or shock), Make it concrete, Make it emotional (fun or music-driven), and Tell a story.

Create a Black Opps Team

We want to be successful, right. And to be successful, we need to use all the tools available at our disposal. So, we’ll “borrow” the same tactics used for the 2016 election and are likely being used by the Kremlin-backed Internet Research Agency and the Chinese social media trolls and look for ways to subvert their efforts.

This will require adding more than a few social media experts to our team. It may also require creating an app that will aggregate all of our positive news and allow us to speak directly to users.

Finally, Realize This Will Work

We have a grand vision, our strategy, and a preliminary list of tactics.

But you have to realize all of this is our job. Making content that engages. Connecting people with that content. Building content that attracts people. Creating a community. Serving that community.

That’s our job as storytellers. We must make it visible. And reinforce it through repetition.

Are you ready to go on this journey?

[1] $100 million sounds like a lot of money. But the amount pales in comparison to the billions funneled through think tanks, lobbying groups, public policy organizations, influencers, and political candidates and front groups paid to create doubt and denial. That money has been invested for decades to make the U.S. a more conservative, science-denying, divided place.

[2] TL:DR Quibi is a short-form mobile streaming service that raised $1.75 billion and has failed spectacularly in gaining traction.

Please Kill Me (Review)

Pedro Paramo is the book I’ve most given away. It’s a thin, easy to read, very influential novel. It will haunt you.

The second book I’ve most given away is Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain’s Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk.

Through a series of alternating interviews, PKM traces the history of punk. From New York to Detroit to New York and London.

Picture New York City in the mid-1970s. Gritty. Dirty. DangerousThe City was on the verge of bankruptcy.[1]

In contrast, rock ‘n’ roll in the mid-1970s is bloated and growing fatter.

On the East Side of Manhattan (on 47th Street to be exact), Andy Warhol’s factory births The Velvet Underground.

The Velvets play a stripped down version of rock ‘n’ roll mixed with avant garde sounds. They sing about mature subject matter: bondage, transvestites, and scoring drugs.

They go on to inspire many bands.

Halfway across the country, Detroit births the MC5 and The Stooges.

The MC5 are known for their aggressive, provocative, loud performances, which contrast hippie, flower-power bands.

The Stooges‘ Iggy Pop’s over-the-top performances earn him the moniker, “Godfather of Punk.”

The stage for punk is set long before it arrives at CBGBs, a club on the Bowery. [2]

New York births The New York Dolls, Blondie, the Dead Boys, the Patti Smith Group, the Ramones, and Talking Heads.

PKM’s cast of characters is extensive AND exhausting: Warhol, David Bowie, David Byrne, Debbie Harry, Malcolm McClaren, Iggy Pop, Dee Dee and Joey Ramone, Lou Reed, and Patti Smith, plus actors (Jim Belushi!), authors, artists, band members and poets.

All of them speaking in their own voices.

Explaining how bands were formed, who always had drugs, who knew how to play music, who didn’t.

To me, the book is an important lesson in making a scene.

By that I don’t mean “create a public display or disturbance” or “complain noisily and display bad behavior” (though punks did both).

I mean surround yourself with people who inspire you, help each other, do great work, perform together, and rinse and repeat.

Some of the people in PKM had talent. Others didn’t. Some used a lot of drugs. There were fights and stolen loves.

You might not want to be friends with several. Many of their stories are tragic. People died.

Yet, they came together to create something awesome.

By the dawn of the seventies, the philosophy was that you couldn’t do anything without a lot of money. So my philosophy was back to, “Fuck you, we don’t care if we can’t play and don’t have very good instruments. We’re still doing it because we think you’re a bunch of cunts.” – Malcolm McClaren

You can read this book straight through and enjoy the hell out of it.

You could also read it as a science fiction novel and enjoy it in a different way.

In my humble opinion, PKM is the book you read BEFORE Jessica’s Livingston’s Founders at Work: Stories of Startups Early Days, though the subject matter and format are different.

Livingston’s book (which I still come across on startup founders’ desks) is about changing business; McNeil and McCain’s book is about changing culture.

Updated 4/7/2108 to include footnotes.

[1] New York City today is nothing compared to what it was in the mid-1970s. Even in the late-1980s, when I first visited, New York still had an edge. Today, New York City is a sanatized shopping mall.

[2] I was lucky enough to see a few bands at CBGBs: Sonic Youth, The Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black, Sham 69 (where EVERYONE knew EVERY song and sang aloud), Atari Teenage Riot, Bikini Kill, Batmobile, and a show that featured a who’s who of the California bands I’d seen live in L.A.: Circle Jerks, D.I., and 45 Grave. Today, CBGBs site houses a John Varvatos shoe store. R.I.P.

[3] The Blondie image is one of my favorites and it’s from band member Chris Stein who you can follow on Instagram.

[4] The Los Angeles (or West Coast) version of this book is Marc Spitz’ We’ve Got the Neutron Bomb. Sadly, it doesn’t come close to being as exciting or exhaustive or definitive as PKM.

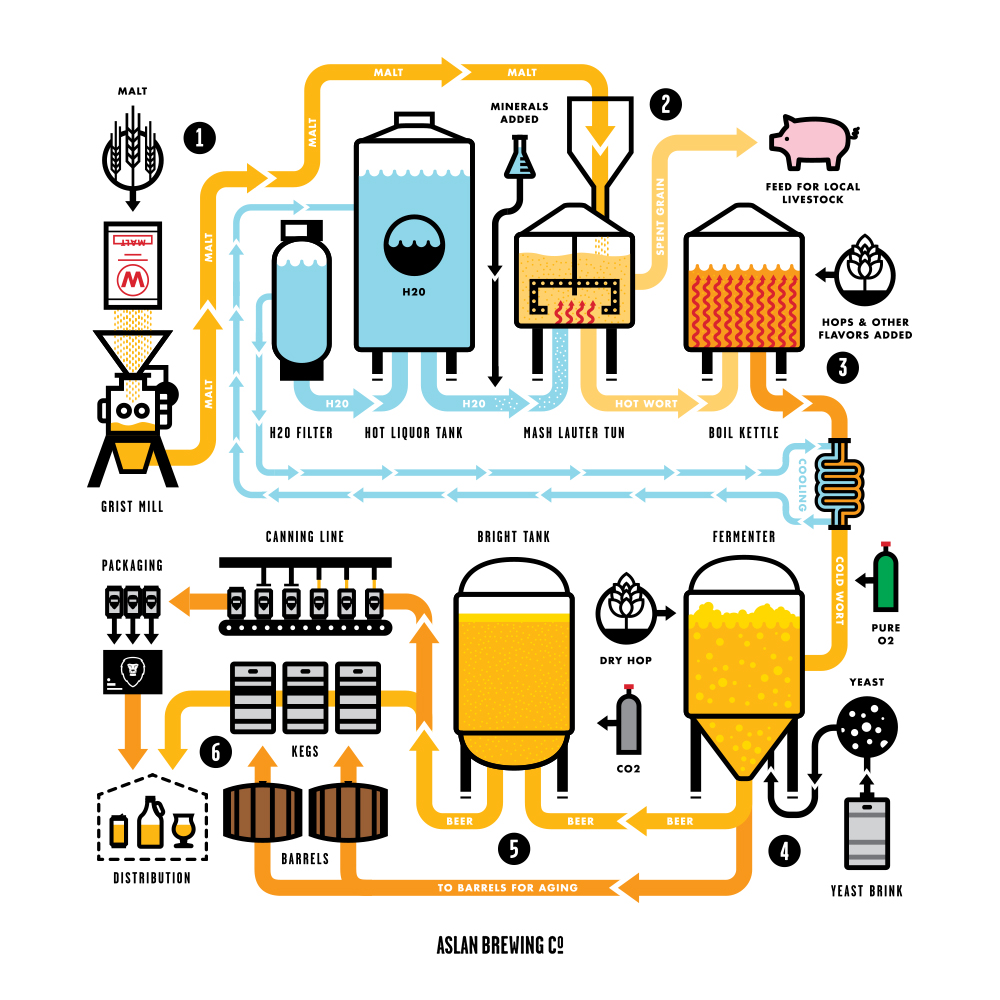

Brewing Stories to Drive the Bioeconomy

When I speak with non-technical, non-biotech audiences, I’m always looking for a place where we can start the conversation. These days, it’s with brewing.

When I speak with non-technical, non-biotech audiences, I’m always looking for a place where we can start the conversation. These days, it’s with brewing.

Most people, remember, know little-to-nothing about the way biology is impacting their lives. Most people, I believe, want to know.

So these days, I start the conversation with beer and wine. Both involve taking ingredients that have little value on their own. But add biology, shake or stir, wait a while, and you end up with beer or bourbon or mezcal or wine. Plus, every culture has a tradition of fermentation so most people can relate. Last week, Bloomberg ran a story titled, In the Future, There Will Be a Distillery on Every Corner.The article points out that breweries and distilleries were among the manufacturing industries creating the most jobs.

In fact, they were the number 2 manufacturing industries with the most job growth. (Plastic products (!) were number one – let’s do something about that.)

Over the past decade, the brewing, distilling and wine-making industries have seen an explosion of new entrants. Consumers looking for unique products and professionals looking for fulfilling jobs are driving growth.The article makes another important point: craftsmanship is making a comeback in the US.

I see this as a biotechnology story, a distributed biological manufacturing story, and an important story about creating jobs.

If I can get someone to understand the brewing story, I can start talking about breweries as bio-reactors, factories where we use biology to create even more valuable products. Then, I tell the stories Bolt Threads brewing spider silk and Modern Meadow printing leather.I talk about Ginkgo Bioworks building the micro-organisms that will enable the transition from brewing to bioprocessing.

As my final example, I like to tell the story of Stanford professor Christine Smolke and her team. They genetically engineered yeast to produce opioids.In doing so, they have the potential to improve access to painkillers in places where they are unavailable.

How do you explain the stories of biotechnology? [If you’re interested in the growth of the craft-beer boom, the Bloomberg article includes a rabbit hole of links to other articles on the craft-beer boom, small distilleries, and craft other stuff.]

Devo

“You’re into Devo?” he asked. “Aren’t you?”

His tone mocking.

As if there was something wrong with it.

Because for him, Yeah. Devo was too mainstream. Fake alternative. He was above that, and what he thought they stood for.

“Of course I am,” I answered, thinking, Whatanasshole. “How could you not be?”

Because at the time there was no voice for the weird.

Used to be you were walking down the street, looked too weird, too punk, someone’d stick their head out of their car window and yell, “DEVO!”

It was the catch-all for anyone, anything so weird it still didn’t have a definition.

But Devo has been having a great time since the late-1970s. Laughing all the way to the bank probably because they’re still touring and their influence is widespread. It’s more than likely you heard something today that was touched by Devo and their commercial music spin-off Mutato Muzika.

So, How did Devo influence you?

Yeast Engineering and Apple Clinics

This week I’ve been thinking a lot about this MIT Technology Review article on writing the yeast genome. The article profiles NYU’s Jef Boeke, one of the founders and leaders of Genome Project write (GP-write). Writing a genome, which is still expensive, will drive advances across many fields (I’ve written about this project in the past and predicted – incorrectly – that the scientists would be finished by the end of last year.)

Healthcare is broken. It’s expensive, eats up a significant part of our gross domestic product, and entering the healthcare system is no fun. Just think about the forms you have to fill out every time you visit a new doctor. The news that Apple is creating medical clinics for its employees (and to test new products) is very very interesting. If you believe that Apple was instrumental in designing technology that is easier to use (and I do), then for sure they will create a healthcare experience that many of us will crave.

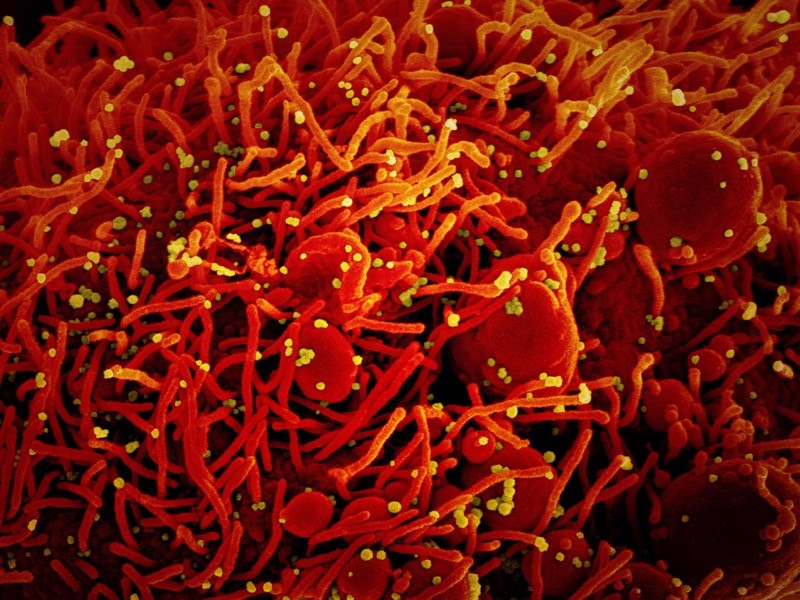

Image Caption:

[1] Colored scanning electron micrograph of lab-grown baker’s yeast.